Detroit History: A Seed to Change

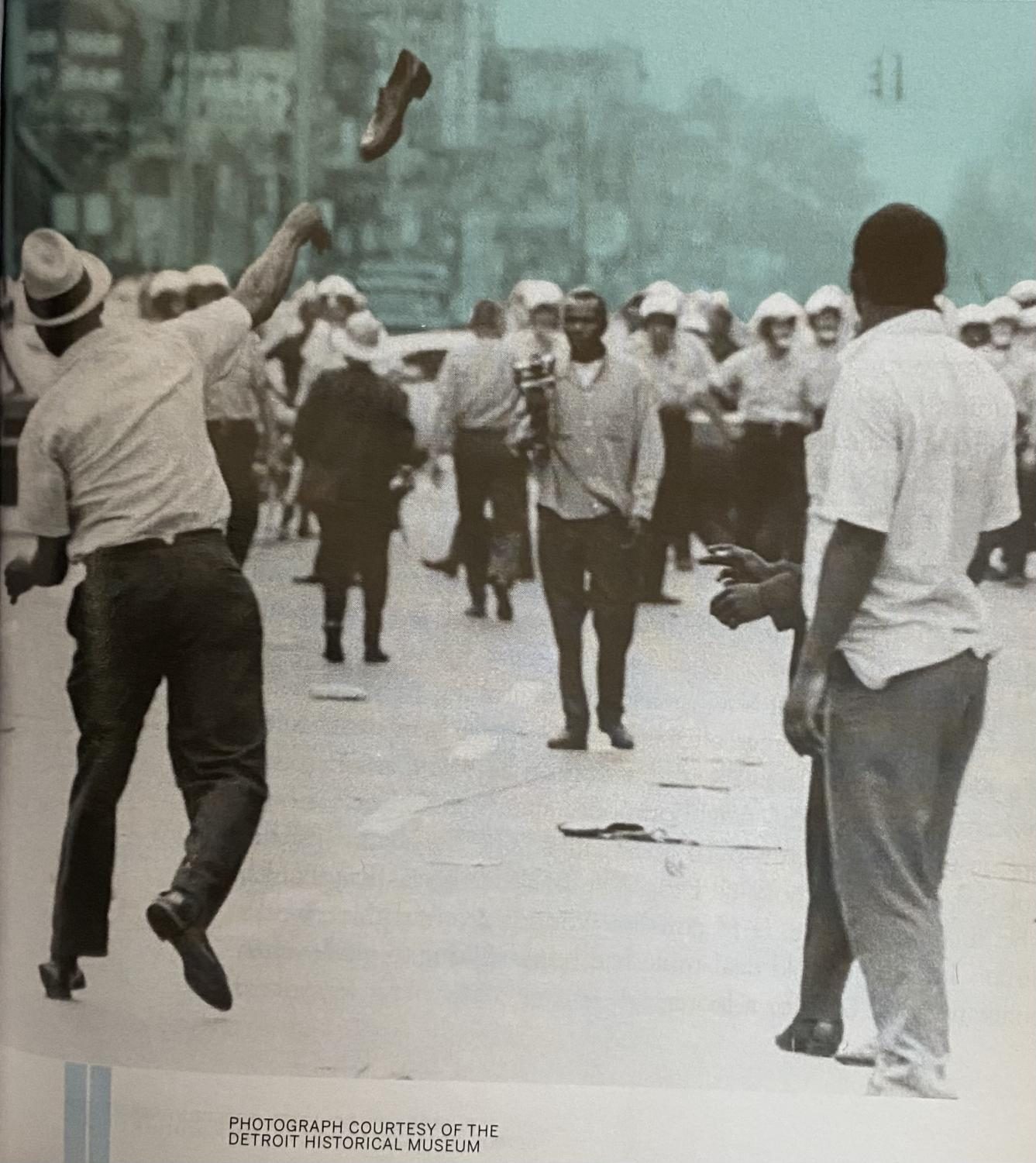

Mack Seyburn of Florida stands guard to prevent looting of the businesses on Mack Avenue near Belvidere Street on Detroit’s East Side.

The other day, my mom and I took a drive to downtown Detroit; we were going to check out an edgy la-dolce-vita-inspired boutique located at the heart of the city. As we drove down Woodward Avenue, I stared aimlessly out of the passenger-side window. Just as my eyes began to fall into their familiar routine of glossing over the passing scenery, a distinct building intervened and caught my attention.

It was a cold day out. The snow that had landed on the street was being spun into whimsical whirlpools by each car that whizzed past it. Pedestrians bundled in parkas and scarves walked hurriedly along the sidewalks, trying to escape the cold, sharp weather. Behind them was a bulwark of buildings. Each one stood stoically, unaffected by the cold weather. The building that gripped my attention was a ravaged and broken home. It stood apart for its looks; there was history in its singed wood and perishing foundation. I didn’t know what that history was, but I wondered. Just then, my reverie was broken by my mom announcing that we had arrived at our destination.

Once I got home that night, I immediately picked up where my thoughts had left off wondering about that resilient home’s past. What event could have caused that 1950s-style home to be seared? This curiosity prompted me to do a little research. A quick Google search led me to a possible explanation: the home may have been among the 1,400 buildings that were burned down during the 1967 Detroit race rebellion. And whether or not this was true, or the burns had just been a result of petty arson, or a kitchen fire, that didn’t really matter. The important thing was reading about the rebellion forced me to acknowledge how little I actually knew about Detroit history. In light of this, I read on, and incidentally stumbled upon an article that answered a question I hadn’t ever thought to ask. The article was “The Anatomy of Detroit’s Decline”, and it was the key that entered me into a room filled with all of the fascinating, yet unsettling, skeletons that the city has in its closet.

With each facet of local history that I uncovered, I grew increasingly frustrated by how little of it I had previously learned about. I was aware of epochs like the Gilded Age and the Civil Rights Movement because of my studies in U.S. History class. Still, I had not heard of half of the greatly influential events that occurred during those times. I knew next to nothing about our state’s former capital: a once-thriving and prosperous metropolis only fifteen miles away. This ignorance felt like a great deprivation, and I quickly recognized it as a failure on my high school’s part.

All of my frustration and annoyance mixed with a profound intrigue about local history inspired me to take action. I dove right in and set out on some interviews with Berkley students to discover if any Berkley courses have provided them with a rich understanding of Detroit history. I spoke with five different students from three different grades: Sophia Baron (sophomore), Sydney Page (junior), Joshua Bianca (junior), Devin Price (senior), and Zeddicus Ball (senior). All of these students had taken the same mandatory history course as I had freshman year, U.S. History. Additionally, I specifically chose to include Page and Ball because the former had taken African American Literature, and the latter frequently travels down to Detroit in his spare time and claims to have a deep interest in the city.

I based my interview questions off of my personal research. I focused on various events which were repeatedly cited as significant events in Detroit history. The first question I asked the students was, “What do you know about Detroit’s automotive industry? And what were some of the positive/negative impacts that the industry had on Detroit?” I was hoping that in their responses, the students would mention something about either how Detroit’s reliance on the automotive industry as a single industry caused economic issues for the city, or how it contributed to racial inequalities.

Most of the students’ answers were pretty consistent, although not in meeting this aim. Baron, Page, and Price all admitted that they didn’t know much about Detroit’s automotive industry aside from that it was large, and they also weren’t sure about the ways that it had affected the city. Bianca, on the other hand, had a little bit more to say. He presumed that having a “bumping car industry had to have been a good thing because it made Detroit known for something… but it also probably had to have caused some issues for the city.” To back up his latter claim, he referenced an article that he read (in his own time) explaining the potentially negative impacts that automotive industries can have on urbanization within cities. He divulged that Detroit was listed as the number one example of these impacts, but he couldn’t remember specifically what they were.

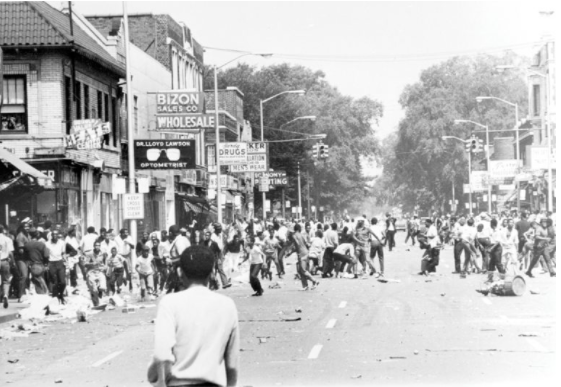

Next, I asked, “What circumstances/events led to the 1967 Detroit rebellion? What impact did it have on the city of Detroit, and how do we feel that impact today? Most obviously, I was hoping that answers would include references to the physical destruction that resulted from the rebellion, and the lingering examples of such destruction (possibly such as the home that inspired this entire article.) However, I was also hoping to hear mention of police brutality, housing discrimination, segregated society, or any of the other things that had galvanized Black community members. Yet, out of the lot, only Bianca and Ball were able to identify that the rebellion was the result of growing racial tensions within the city. Ball was the only one that commented on how the impacts of the rebellion are felt today.

“I still think there’s a lot of tension there, although it’s a lot better than it used to be,” he said, “There has been a lot of economic growth happening… But, still, there’s a lot of tension, especially between ‘the powers that be’ like the government and the police force, and the actual Black community in Detroit.” Ball continued, “All of this leads to conflict, and that causes really unfortunate things to happen.”

Notably, both Ball and Bianca admitted that they acquired their knowledge about the event outside of school through their own investigations. While Baron, Page, and Price said that they knew little to nothing about the event, nor how its impacts are felt today.

I then asked the students, “Have you ever heard of white flight? And if you have, what do you know about how that occurred within Detroit around the 70s?” My rationale behind asking about white flight was that it is an indicative example of the festering racism that was prevalent within 20th century Detroit. And the responses were similar to the last question: uninformed. Sophomore Baron explained that the term “white flight” sounded familiar while Page and Price both admitted that they were not familiar with it. Accordingly, none of them knew what it meant. Again, the only student who had a more-or-less-developed response was Ball who explained white flight as, “A massive outflux of people that resulted in Detroit losing a huge amount of its population.” He added, “The city is still rebuilding from that.”

And although my findings were already speaking for themselves, I next asked students, “How much of your knowledge of Detroit comes from school? And how much of it comes from other sources?” Baron replied, “Honestly, all of it comes from outside of school.” She explained that her uncle is very interested in Detroit, and he likes to teach her about how far the city has come and how the public’s perception of the city has changed. Similarly, Bianca said, “Literally none of my knowledge [of Detroit] comes from Berkley High School. I don’t think that I have ever actually learned about any of these [referencing the topics that we discussed in the interview].”

Bianca then went on to explain that his knowledge comes from “being someone who lives in the general vicinity of this very historical place [Detroit].” Page’s response also followed a similar trend. She said, “I don’t think any of my knowledge actually comes from school. We haven’t really learned much about Detroit in any of the classes I’ve taken.” Ball agreed that none of his knowledge comes from BHS. Instead, he explained it comes from his own ventures into the city.

“I go down to Detroit to check out the places and learn about the city’s architecture and the city’s history… A lot of those [things I explore] are things that I’m interested in and willing to go out of my way to find out about.”

This last anecdote from Ball inspired me to include an additional question in my remaining interviews: “Would you be interested in taking a course at Berkley about Detroit history?” I figured that if Ball is so interested in Detroit that he is willing to take extra measures to teach himself about the city, then maybe other students at Berkley have a similar interest in the city, but they simply don’t learn about it because of the current inconvenience that doing so causes for them. And, just as I suspected, the two remaining interviewees, Bianca and Baron, both unhesitantly replied that they would be very interested in a course like this, and would likely take it if it was an option.

After all of my interviews, I felt that I could unequivocally conclude that Berkley students are not being taught enough in school to show that they have a thorough understanding of Detroit history. So, why are lessons about local history slipping through the cracks? To find out, I went to the top drawer and interviewed the U.S. History teachers, Mrs. Simone and Mrs. Church, and the African American Literature teacher, Mr. Cooper. I asked each of them questions to try to uncover whether BHS students’ gap in knowledge finds its roots in their classrooms.

Right off the bat, I was told the same two things by all of the teachers. The first thing was that their curricula are created by the Michigan Department of Education which means that their teachings need to follow a fairly stringent outline. Additionally, that outline, unfortunately, does not carve out space for teachers to be able to make in-depth local connections to a lot of the material that they teach. The second thing they explained was, despite this, all of them still make concerted efforts to incorporate more Detroit-centric material into their teachings. Mrs. Simone explained how exactly they do this in U.S. History.

She said, “We use Detroit as a primary example in [our teachings about] the Roaring Twenties…using both Prohibition and Henry Ford. We naturally, luckily, have a standard that has Henry Ford in it, and then we get to push that.”

She continued, “Then when we get to our civil rights unit, the magazine that you have in front of you [an Hour magazine issue commemorating the 1967 rebellion] is an example of how we take a very Detroit-focused look because many of the race riots happened here.” She continued, “We also go to our African American History Museum–when we are allowed to travel in museums–and that has a great Detroit-focus as well.”

Mrs. Church then chimed in to clarify how they use the aforementioned magazines; they hand them out during class for the children to look through on their own. Additionally, they only incorporated this into their curriculum a few years ago which could explain why some of the upperclassmen were not very familiar with the rebellion.

I asked what inspired them all of a sudden to try and take this closer look at Detroit.

Mrs. Church answered, “I think that doing that makes the material a little more real. So, anytime we can find some personal or local connections, students tend to be a little more engaged…That is why anytime that we can make a Detroit connection, I think that we try to.”

Mrs. Simone then built on this thought, saying, “It also gives students a chance to understand the communities that they live in. So if you choose to live in the metro-Detroit area for the rest of your life, it will be critical for you to understand things, like why we are so segregated.”

Beyond this, Mr. Cooper explained his own reasons for attempting to include as much Detroit history as possible into his African American Literature course. He feels that it is important for all students to learn about local history. He explained, “[local history] involves everyone. The suburbs and the city are all connected and related, and you don’t realize it, but their histories are also connected.”

He also emphasized that he talks about Detroit history whenever he can in both of his classes. He said for AA Lit, “As we come up to our studies of the Civil Rights Movement, I always like to include any kind of local connection because I feel like that makes it a lot more interesting and relevant for the students.” He also does this for his English 10 class. “We read a book in Honors 10 that kind of has to do with red-lining…and so I talk to students about how that relates to Detroit and even to us here in Berkley.”

Despite these efforts, Mr. Cooper still feels that there are misconceptions about Detroit history that are ingrained within society that are hard for him to dispel with the limited freedom that he has to focus his teachings on Detroit. He gave an example of one of these misconceptions, he said (referring to the 1967 race rebellions), “People think that Black people tore the city up in ‘67 and they assume that it’s the reason why things are the way they are right now. People really don’t look into what was going on during that time, and what caused the rebellion.” He continued, “I think that it’s really all about providing students with the full story which will help them to have a clear understanding of why things are the way they are today.”

When I asked Mr. Cooper if he thinks that Berkley should have a class about Detroit history, he agreed wholeheartedly. “I think that would be a phenomenal idea. And I think that in order to give it the justice that it really deserves, then Detroit history would need to have its own class.”

His closing statement reminded me of something that Mrs. Simone mentioned at the end of her interview. She said, “It is difficult. It’s difficult to do both macro and micro views. We’re hoping, though, that we will instill a love of curiosity about history and [create] a drive for students, in their local areas, to be able to say ‘hm I wonder what’s going on there.’”

I suppose this means that the burnt down home was my seed and, hopefully, this article can be yours. Because, yes, I have certainly accomplished what I set out to do in writing this article: I found good evidence that proves students don’t know a lot about Detroit’s history. But, that said, learning more about our local history and conducting these interviews with students has inspired me to build on my original goal. My hope is now that this article can help inspire curiosity among others about Detroit history.

Mrs. Simone mentioned another thing in our interview that stuck with me. She said, “Understanding your local history can help you to decide if you want to continue the way we are going, or to determine that change is necessary.” This too can happen within Berkley High School. So, my question to you is, what do you want to do with the information here in this article? Would you like to continue on the way that things are currently going? With teachers scrambling to educate students about Detroit through the patchwork of material that their curricula permits them to cover. Or will we determine that change is necessary? Will we find a way to better honor the underlying curiosity that Berkley students have about Detroit? And for me personally, I’m wondering, how soon can we get started?

Hello everybody:) my name is Raynah Jacobs. I have had the pleasure of being on the Berkley Writing for Publication staff for Four years now....